Dear Gen Xer,

Testing for the Salsa Rio had gone through the roof. Now Frito-Lay needed a campaign to match the zing of its brand new chip. Unfortunately, their previous mascot, Frito Bandito (voiced by cartoon legend Mel Blanc) had been forced to retire years ago following complaints from the Hispanic community that he was nothing more than a racist stereotype.

Frito-Lay hired Tracy-Locke to help them launch the Salsa Rio. They already had the jingle down. All they needed was a voice.

The creative team at Tracy-Locke auditioned a number of professional singers, settling eventually on a midlist artist with a deep bluesy tenor.

The higher-ups hated it.

The voice was too smooth. Too slick and refined. The Salsa Rio has an edge, they said. Find us a singer like that.

Tracy-Locke expanded their search.

Caught in their net was Stephen Carter. He’d been gigging professionally the last ten years and was familiar with the song Step Right Up, on which the jingle was based. As a matter of fact, Carter’s impression of the singer was so uncanny, it had caused the creative team to do a double-take.

It also raised flags for David Brenner. He was the executive producer at Tracy-Locke and he worried about legal troubles down the line. He asked Carter to dial his impression of the singer back and recorded the jingle again. The results were not good.

Brenner expressed his concerns to Robert Grossman - managing vice-president at Tracy-Locke and executive on the Frito-Lay account. Grossman told Brenner he’d think it over. Brenner, meanwhile, recorded another version of the jingle with a different singer. He wanted a backup, just in case.

Grossman consulted with Tracy-Locke’s attorney on the day the commercial was scheduled to air. The attorney didn’t think there’d be a problem, seeing as a singer’s vocal style wasn’t protected by law.

Grossman played both jingles for the brass at Frito-Lay: Carter’s version and the backup version Brenner had recorded with another singer.

The brass chose Carter.

The commercial aired on over 250 stations in 61 markets during September and October of 1988.

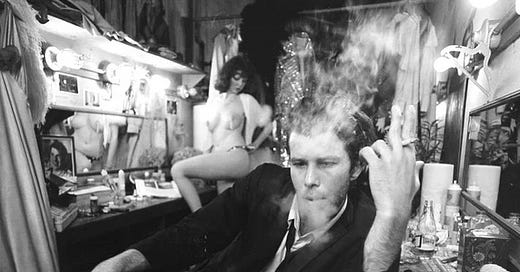

Tom Waits was at one of those stations - KCRW in Los Angeles - when he heard what he would later refer to as “this corn chip sermon”.

“Somebody had studied me a little too close. It was the equivalent of all the scars, dimples, the lines all being in the same place. . . . It was a little spooky.” – Tom Waits

Waits had been outspoken against doing commercials since the start of his career. He felt such practices diminished the song, as well as the artist. “I’d rather have a hot lead enema,” he said.

His beliefs weren’t enough to stop him, however, from doing a commercial for Ralston Purina in 1981.

“I was down on my luck and needed the money. So I agreed to do a voice-over for a dog food commercial. I always liked dogs.” – Tom Waits

Regardless of his rationalization, Waits felt like he’d betrayed himself and vowed to never do it again. He spent the next seven years making albums, touring the country, rejecting commercials from tennis shoes to motor homes, and grinding out a reputation as an artist who values integrity.

Then this shit with Salsa Rio.

"It embarrassed me. I had to call all my friends, that if they hear this thing, please be informed this is not me. I was on the phone for days. I also had people calling me saying, Gee, Tom, I heard the new Doritos ad." – Tom Waits

Waits sued Frito-Lay Inc. and Tracy-Locke Inc. in November 1988 for false endorsement and misappropriation of his voice. He argued that the commercial had humiliated him and made him look like a hypocrite: a misrepresentation that had the potential of ruining his artistic reputation.

Waits didn’t include Carter in his suit. He didn’t have to. Carter felt so terribly for impersonating Waits, he became one of his strongest witnesses.

The irony is that Step Right Up – the song the Salsa Rio jingle is based on - is essentially about hucksterism. It satirizes the very peddling that Frito-Lay and Tracy-Locke engage in every day.

"I get it all the time, and they offer people a whole lot of money. Unfortunately I don't want to get on the bandwagon. You know, when a guy is singing to me about toilet paper - you may need the money but, I mean, rob a 7-11! Do something with dignity and save us all the trouble of peeing on your grave. I don't want to rail at length here, but it's like a fistula for me. If you subscribe to your personal mythology, to the point where you do your own work, and then somebody puts decals over it, it no longer carries the same weight. I have been offered money and all that, and then there's the people that imitate me too. I really am against people who allow their music to be nothing more than a jingle for jeans or Bud. But I say, "Good, okay, now I know who you are." 'Cause it's always money. There have been tours endorsed, encouraged and financed by Miller, and I say, "Why don't you just get an office at Miller? Start really workin' for the guy." I just hate it... The advertisers are banking on your credibility, but the problem is it's no longer yours. Videos did a lot of that because they created pictures and that style was immediately adopted, or aborted, by advertising. They didn't even wait for it to grow up. And it's funny, but they're banking on the fact that people won't really notice. So they should be exposed. They should be fined! [Bangs his fist on the table] I hate all of the people that do it! All of you guys! You're sissies!" – excerpt from Tom Waits’ testimony

The four-week trial ended with a jury awarding Waits $2.6 million in damages:

- $375,000 in compensatory damages for infringement of the right of publicity/false endorsement (including $100,000 for the fair market value of Waits' services under the Lanham Act claim; $200,000 for injury to his peace, happiness, and feelings; $75,000 for injury to his goodwill, professional standing, and future publicity value)

- $2,000,000 in punitive damages for voice misappropriation ($1.5 million against Tracy-Locke and $500,000 against Frito-Lay)

- $100,000 damages for violation of the Lanham Act

- $125,000 attorney fees

It was the first time punitive damages were awarded to a singer for having their reputation diminished by advertising. Not too shabby for a guy who hadn’t made the best first impression.

“The first time I saw him I thought this was a criminal case and he was a criminal, and when he left the court the first time, we thought he was getting away. But now we love his music and him. . . . His music is deep.” – George Chavez, juror

Heart Attack and Mine

Three and a half years after Frito-Lay, Waits was back in court again.

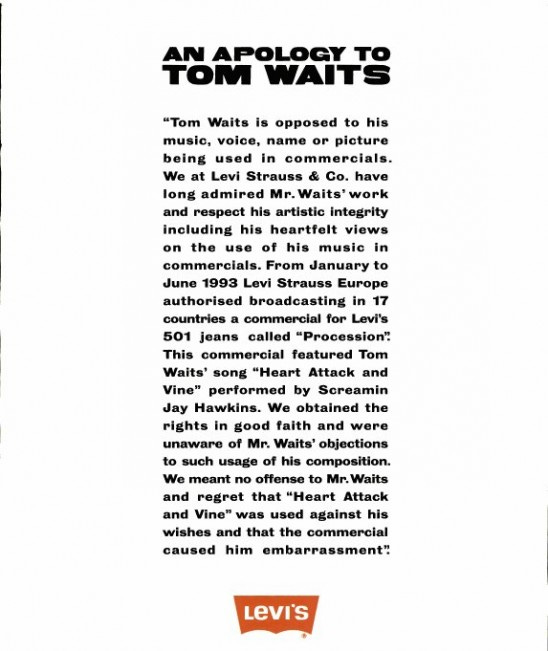

One of his songs – a Screamin’ Jay Hawkins cover of Heartattack and Vine – had appeared in a commercial for Levi’s jeans.

Waits was furious. Especially since the copyright to the song belonged to Herb Cohen and his publishing company Third Story Music, Inc.

“I had a manager when I was a kid, I threw in with a guy named Herbie Cohen, who worked with Zappa. I wanted a big bruiser, the tough guy in the neighborhood, and I got it.” – Tom Waits

Waits separated from Cohen in 1982, but Cohen continued to own the rights to Waits’ early work, including the song Heartattack and Vine. Cohen licensed it to Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, then released Hawkins’ album Black Music for White People through his record label, Bizarre/Planet Records. A couple of years later, Levi’s called Cohen.

The Screamin’ Jay Hawkins version of Heartattack and Vine appeared in a commercial called ‘Procession’ in January 1993.

The commercial was broadcast in 17 countries across Europe. A short while later, Heartattack and Vine was released on a Levi’s compilation CD in Holland, Germany, Austria, and the UK.

Waits sued Third Story Music in May 1993 for allowing Levi’s and its UK agency Bartle Bogle Hegarty to use Heartattack and Vine without his permission.

The court ruled in favor of Waits.

He was awarded a fraction of the money he’d been seeking, though perhaps Waits took a little solace in the official apology Levi Strauss and Company offered him courtesy of a full-page ad in Billboard.

“Songs carry emotional information and some transport us back to a poignant time, place or event in our lives. It's no wonder a corporation would want to hitch a ride on the spell these songs cast and encourage you to buy soft drinks, underwear or automobiles while you're in the trance. Artists who take money for ads poison and pervert their songs. It reduces them to the level of a jingle, a word that describes the sound of change in your pocket, which is what your songs become. Remember, when you sell your songs for commercials, you are selling your audience as well.” – Tom Waits

Innocent When You Scheme

Audi-Spain released a commercial for its Audi A4 in the spring of 2000. It featured music that appeared to have been influenced by Tom Waits’ Innocent When You Dream. The composition was punctuated by a gravelly-voiced singer.

The commercial won the Grand Prix award at the Ibero-American Advertising Festival. Corks were popped. Bubbly was guzzled. Marketing managers made merry.

Three years passed before Waits found out.

He heard about it from Spanish fans posting on various fan-related sites. They believed he’d performed the song for Audi and wanted to know why.

Waits was outraged.

He’d already been approached by Tandem Campmany Guasch DDB Spain (the production company responsible for the commercial) and had refused their request to use his song Innocent When You Dream. Little did he know that they’d simply hired an impersonator instead.

"It's part of an artist's odyssey, discovering your own voice and struggling to find the combination of qualities that makes you unique. It's kind of like your face, your identity. Now I've got these unscrupulous doppelgängers out there - my evil twin who is undermining every move I make." – Tom Waits

The case was decided by an appeals court in Barcelona, who awarded Waits 36,000 EUR in damages for copyright infringement, as well as an additional 30,000 EUR for violation of his “moral rights” as an artist.

It was a landmark victory: the first time such moral rights (i.e. acknowledging an artist's voice as their creative work and protecting the personality and reputation of artists) had ever been established in a Spanish court of law.

"Now they understand the words to the song better. It wasn't 'Innocent When You Scheme' it was 'Innocent When You Dream.'" – Tom Waits

Yeah, but that TruCoat

Waits must have thought it was Groundhog’s Day when fans began to contact his label a few years later in 2006. They wanted to know why he’d done a car commercial. No, not Audi. Opel.

Waits learned that Adam Opel AG (a European subsidiary of General Motors) had launched a campaign for its Opel Zafira in April 2005. Included in the campaign was a series of commercials which were broadcast in Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. They featured the Brahms composition Wiegenlied (“Lullaby”), and were accompanied by a singer who sounded familiar.

Opel had approached Waits in the past. To nobody’s surprise, he’d refused their offer. When he found out that his voice was being impersonated yet again, Waits filed suit against General Motors Opel and ad agency McCann Erickson.

"Apparently, the highest compliment our culture grants artists nowadays is to be in an ad -- ideally naked and purring on the hood of a new car. I have adamantly and repeatedly refused this dubious honor. Currently accepting in my absence is my German doppelganger. While the court can't make me active in radio, I am asking it to make me radioactive to advertisers.” – Tom Waits

Opel played dumb.

"We actually are surprised about the fact that Tom Waits considers the music that goes with the current TV commercial 'Lullaby' for a range of Opel cars as a potential misuse of his voice and style of singing." – Opel official statement

Opel also denied approaching Waits in the past. Waits responded by handing over documents to the New York Times that showed his publishing company had been approached by Opel in 2004 via an agency in Amsterdam. The documents also showed that Waits had declined the offer. When the Times asked Opel to comment on the documents Waits had provided, representatives for the company shut their fucking faces.

"If I stole an Opel, Lancia, or Audi, put my name on it and resold it, I'd go to jail. But over there they ask, you say no, and they hire impersonators.” – Tom Waits

Waits went on to clarify that he believed in two kinds of imitation:

"I don't mind if someone wants to try to sound like me to do a show. I get a kick out of that. I make a distinction between people who use the voice as a creative item and people who are selling cigarettes and underwear. It's a big difference. We all know the difference. And it's stealing. They get a lot out of standing next to me, and I just get big legal bills." – Tom Waits

The court sided with Waits again.

Opel was ordered to remove the song from its campaign. The money Waits was awarded has never been disclosed, though it’s been reported that he donated the proceeds to one of the many charities he’s involved with.

“When I was a kid, if I saw an artist I admired doing a commercial, I'd think, "Too bad, he must really need the money." But now it's so pervasive. It's a virus. Artists are lining up to do ads. The money and exposure are too tantalizing for most artists to decline.”

Tom Waits is not most artists. Step right up and try him.

Big fan of Tom Waits (since a gift of "Franks Wild Years" on CD), and yet I'd heard of NONE of this! Good for him for suing the pants off those companies. His voice, phrasing and songs are SO distinctive that copying them is almost foolish, like, "You're asking to be sued!"

Excellent article as always, Sonny! Rock on!

Thank you for the post! Inspiring ✌️🔥