Dear Gen Xer,

Flames flickered from a rooftop on New England Street.

The stretch of quaint Colonial buildings had starred in countless small-town scenes in movies and on television. Workers at Universal Studios Hollywood had been repairing a roof on the set all day, heating asphalt shingles with blowtorches until 3 a.m.

The workers waited, as required, for one full hour after they’d finished. Satisfied that the shingles had cooled, the worn out crew left for home. Forty minutes later, a shingle ignited.

The fire spread quickly, engulfing the equivalent of a city block within a few minutes.

It burned through the backlot’s New York City streetscape, ravaged two sides of Courthouse Square (recognizable from Back to the Future), and continued south to a massive shed that housed an animatronic attraction called King Kong Encounter.

The LA County Fire Department sent more than 400 firefighters to help Universal’s on-site brigade battle the three-alarm blaze. They drafted water from an artificial lake which had featured in Creature from the Black Lagoon, and were buoyed by a pair of helicopters that rained water on the rising flames. All of this was necessary due to the anemic water pressure coming from Universal’s in-house pipes.

Eventually the fire reached a building made of corrugated metal. The 22,320 square-foot warehouse was known as Building 6197. People who worked there called it the Video Vault.

Two-thirds of the vault was used to store film reels, videotapes, and digital video. The other third of the vault, a fenced-off area of 2,400 square feet, served as an archive of some of Universal Music Group’s most valuable material.

Randy Aronson, Senior Director of Vault Operations at Universal Music Group, was awakened at his home in Canyon Country shortly after the fire started. He could see dark clouds of billowing smoke from the Hollywood Freeway. By the time he reached the lot at 5:45 a.m. - roughly an hour after the first shingle caught - the blaze had become an inferno.

Over a dozen fire trucks had formed a ring around the vault. 24 hours would pass before the flames were finally extinguished.

“It was like those end-of-the-world-type movies. I felt like my planet had been destroyed.” – Randy Aronson

The fire made headlines around the world.

All of them focused on the film and video assets that had been housed in the vault. There was no mention of a music archive. Or that UMG, through a series of mergers and acquisitions, had been paying rent on Universal’s lot when the fire struck.

Among the first to mention the music was Nikki Finke for deadline.com, who reported that thousands of original Decca, MCA, and ABC recording masters had been destroyed in the blaze. One of her sources was quoted as saying:

“This is a tremendous loss in music history. A very sad day indeed. It’s too bad they saved the videos that they have backups on instead of the master recordings in which they do not, although they may not have had a choice since the fire had already engulfed much of the music side of the vault.”

A spokesperson for UMG was quick to assure Billboard that:

“We had no loss, thankfully. We moved most of what was formerly stored there earlier this year to our other facilities. Of the small amount that was still there and awaiting to be moved, it had already been digitized so the music will still be around for many years. Moreover, in addition to being digitized, we also had physical back up copies of what was still left at that location, so we were covered.”

UMG claimed that the artists whose work had reportedly been destroyed, ranging from Bing Crosby to Nirvana, had been spared from extinction. White Christmas was safe. Come As You Are was safe. Thank god for that.

Except UMG’s statement sidestepped the real issue at hand: the irretrievable loss of master recordings.

“A master is the truest capture of a piece of recorded music. Sonically, masters can be stunning in their capturing of an event in time. Every copy thereafter is a sonic step away.” Adam Block, former president of Legacy Recordings

The master contains the recording’s details in their purest form: the timbre of a voice, the acoustics of a room, the subtleties of an instrument.

This is why remastered albums are always promoted as such. It signals to the listener that the artists and producers have returned to the original source of the music and brought it up to speed with the day’s technology. It’s what led to the CD boom in the 80’s, when artists’ entire catalogs were released in a brand new format. In order to take advantage of that new format, however, you need to go back to the master recording. Converting copies or digital files up to a higher resolution simply won’t do.

Consider the difference between a painting and a photo of that painting. Same thing applies with masters and copies.

The archive in Building 6197 was UMG’s main storehouse for master recordings on the west coast.

Jody Rosen, a writer for New York Times Magazine, acquired a number of UMG documents related to the fire. He reported that:

“…the vault held analog tape masters dating back as far as the late 1940s, as well as digital masters of more recent vintage. It held multitrack recordings, the raw recorded materials — each part still isolated, the drums and keyboards and strings on separate but adjacent areas of tape — from which mixed or “flat” analog masters are usually assembled. And it held session masters, recordings that were never commercially released.”

Rosen claimed the vault had held master tapes for legendary labels like Decca, Chess, and MCA, Impulse, Geffen, and ABC, as well as Interscope and A&M. There were also myriad subsidiary labels, some of whom had lost their entire catalogs. In one of the documents Rosen procured, UMG claimed “an estimated 500K song titles” had been destroyed.

UMG’s statement that they’d suffered no losses in the fire contradicted their internal reports, as well as the efforts they took to document the assets that had been destroyed. The accounting process was necessary in order for UMG to file a series of insurance claims, as well as a suit of negligence against NBC Universal.

Documenting the losses was easier said than done, however, thanks to decades of sloppiness and neglect. UMG knew which labels and artists had been stored in the vault. But which individual album or song? Which outtake, demo or unreleased track? Whatever had been sitting on those shelves was somewhat of a mystery.

It was unclear, for example, whether the Neil Young recordings that had been destroyed in the fire were safety copies of the albums he’d recorded for Geffen in the 80’s, outtakes from those albums’ sessions, or something else entirely.

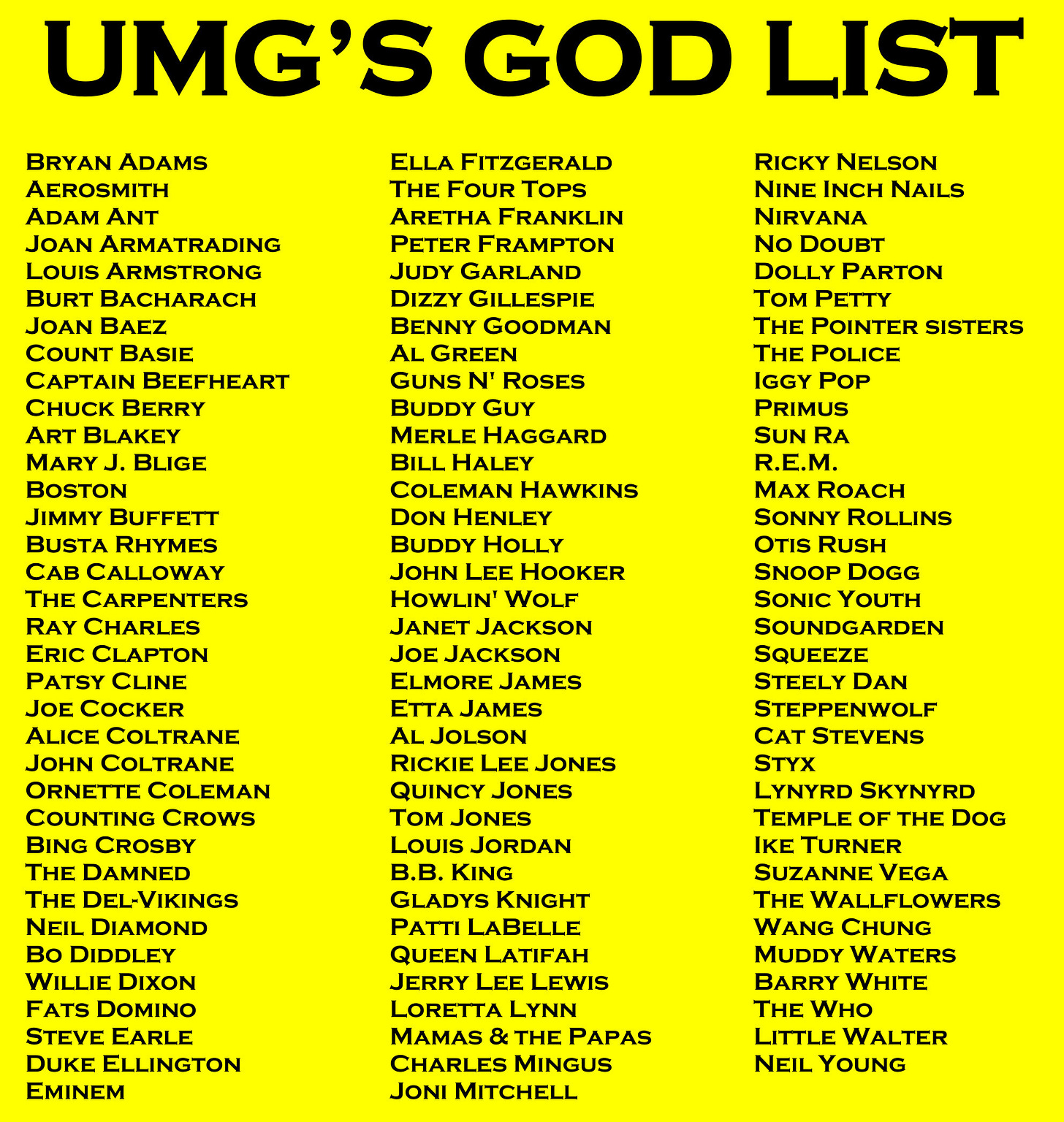

UMG started what they called a “God List” – a complete account of all the artists whose work had been affected by the fire. They also ranked those artists in terms of “value”.

Artists in group A included Muddy Waters, Joni Mitchell, Meat Loaf, Limp Bizkit, Weezer, Whitesnake, Nelly Furtado, White Zombie, Gwen Stefani, Blink 182, and Sublime.

Lumped into group B were Merle Haggard, Captain Beefheart, The Neville Brothers, and The Roots.

UMG released an internal document in March 2009 called “Vault Loss Meeting”. In it was a description of the loss sustained.

“The West Coast Vault perished in its entirety. Lost in the fire was, undoubtedly, a huge musical heritage.”

One week after Rosen’s article, Hole, Soundgarden, and Steve Earle, as well as the estates of Tom Petty and Tupac Shakur, filed a $100 million class action lawsuit against UMG.

The lawsuit claimed that UMG failed to safely archive the artists’ master tapes, then concealed the extent of the damage from them.

“Money is money, but, if UMG had said to its artists: ‘Hey, we will pay you C amount of dollars to sign this record deal, but the irreplaceable multi-track master recordings that you will create may very well be irreparably destroyed because we will not bother to protect them in the slightest possible way,’ I imagine that not that many artists would have signed with UMG.” - Ed McPherson, attorney for the artists

The lawsuit referred to legal documents UMG had filed against its parent company Vivendi, as well as NBC and Universal City Studios, which owned the warehouse on the lot where the UMG vault had burned. Quotes from the document indicate that the vault had been more of a rusty cage than a sanctuary for artists’ work - a well-known firetrap that had needed a new sprinkler system since the last fire on the lot back in 1990.

The lawsuit also stated that UMG failed to inform their artists about the losses accrued in the fire in order to hide the $150 million UMG gained in settlement proceeds and insurance claims. The artists sought damages worth half that amount, as well as half of further losses.

“Our lawsuit on behalf of all affected artists describes a devastating loss of precious master recordings, concealed from the artists for more than a decade. We seek an accounting of every lost master, including outtakes and previously-unreleased material, as well as a fair share of the tens of millions of dollars received by Universal as compensation for the loss.” - Howard King, attorney for the artists

UMG claimed that the losses reported in Rosen’s article had been grossly exaggerated. They also vowed to be transparent while reviewing the extent of the damage. “We owe our artists transparency,” a memo by UMG CEO Lucian Grange read. “We owe them answers. I will ensure that the senior management of this company, starting with me, owns this.”

Who owns what was made perfectly clear a couple of months later, when an attorney for UMG informed the court that:

“Artists have specified rights to royalties. Everything else doesn’t belong to them. Artists don’t have an interest in the masters. Period. Full stop.” - Scott Edelman, attorney for UMG

It brings to mind a quote from the late great Prince, who said while embroiled in a dispute with his record company, “If you don’t own your masters, your master owns you.”

While UMG’s CEO may have felt he owed his artists answers, he wasn’t in any hurry to deliver them. This was made clear when UMG requested a halt in the discovery process, accusing the artists’ attorneys of fishing “for a new angle and new plaintiffs”.

UMG also explained that if they were forced to comply with discovery requests, they:

“…will be harmed by being forced to share hundreds of thousands of pages of documents — including over 10,000 of artists’ confidential recordings agreements with personal and business-sensitive terms to entertainment lawyers representing other artists, without any notice to those artists already under contract — before threshold questions related to both jurisdiction and the sufficiency of Plantiffs’ claims are ruled by this Court.”

Judge John A. Kronstadt denied UMG’s request.

“We are very pleased that, after 11 years, UMG is finally being compelled to tell its artists which masters were destroyed and which masters it told its insurance company were destroyed,” Ed McPherson, attorney for the artists

Two months later, UMG announced that 19 artists had original master tapes and other recordings lost or damaged in the fire.

The artists are:

Bryan Adams, ...And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead, David Baerwald, Beck, Sheryl Crow, Peter Frampton, Jimmy Eat World, Elton John, Michael McDonald, Nirvana, Les Paul, R.E.M., Slayer, Sonic Youth, Soundgarden, The Surfaris, Suzanne Vega, White Zombie, Y&T

Plaintiffs’ attorneys accused UMG of “improper discovery gamesmanship”, as well as trying to have it “both ways”. They pointed to UMG conducting “a substantial investigation of assets lost in the fire” and that the investigation revealed “UMG lost more than 118,000 original music recordings dating back decades.” Attorneys also said that UMG and NBC Universal had reached a confidential agreement, and that UMG had settled an insurance coverage dispute with AXA insurance.

“Universal claimed 17,000 artists were affected by the fire when they were suing for damages. Now that they face a lawsuit by their artists, they claim a mere 19 artists were affected. This discrepancy is inexplicable.” – Howard King, attorney for the artists

UMG argued that plaintiffs’ attorneys were conflating the assets lost in the fire - ranging from safeties to videos to artwork - with the loss of original masters. The numbers the attorneys were referencing were just “well-informed estimates of what overall assets might have been destroyed” and that “UMG knows today that those post-fire working lists were definitively wrong.”

In March 2020, one month after UMG’s announcement, Soundgarden and the estate of Tupac Shakur pulled out of the class-action suit.

No reason was given in the legal filing.

Steve Earle dropped out a week after that. Hole had already left the year before, convinced their work had suffered no losses in the fire of 2008.

That left Jane Petty, Tom Petty’s widow, who continued fighting the suits and ties like her husband had.

On April 6, 2020, Judge John A. Kronstadt dismissed the widow Petty’s claims. His 28-page ruling found that MCA (Tom Petty’s former label; now a part of Universal) owned the rights to his master recordings. Therefore, Mrs. Petty couldn’t sue UMG for “bailment” (or safekeeping).

The case was closed.

The lawsuit was dismissed.

UMG was delighted.

“As we have said all along, the New York Times Magazine articles at the root of this litigation were stunning in their overstatement and inaccuracy.” – statement from UMG

Jake Silverstein, editor at New York Times Magazine, defended the piece that had sparked so much controversy:

“We stand by Jody Rosen’s reporting. This ruling does not refute or question the veracity of what we reported: that, contrary to UMG’s continued effort to downplay the event, thousands of recordings were lost in the 2008 fire.”

So who do we believe?

The Times or UMG?

The media or the music industry?

They’ve lied to us so many times it’s easy (and understandable) to dismiss them both as full of shit.

I’d like to believe the artists involved, but they dropped out one by one, some in satisfaction, others in silence, leaving us all with questions that remain unanswered to this day.

Did they lose their masters? Were they paid to keep their mouths shut? Or is it true that they don’t own their master recordings, so whether they wound up losing them in the fire is literally none of their business.

Until we know more, I’m putting my faith in Randy Aronson. He’s the former director of the UMG vault, who felt like his planet had been destroyed when he arrived on the morning of June 1st, 2008 and saw the hours, days, and years he’d devoted to protecting some of the world’s most valuable music go up in a cloud of smoke.

Aronson had worked in the vault since 1985. The archive was a shambles then, home to thousands upon thousands of tapes that were improperly labeled, stored or shelved.

Aronson knew nothing about preservation then. But he learned his craft “tape by tape”, starstruck by the list of artists whose work was in his charge. Ella Fitzgerald. Chuck Berry. Buddy Holly. Aretha Franklin. The names were enough to make one faint. The thought of their music being lost forever was inconceivable.

Yet Aronson is convinced that’s exactly what happened. He would know better than anyone else what was in that vault. Aronson’s the one, after all, who served as witness for UMG when they claimed the loss of “more than 118,000 original music recordings” for insurance purposes.

Even worse than the tragic loss the music world has surely suffered is the loss Aronson says will always remain a mystery:

“So many things would come to the vault straight from studios and get shelved. You know, Nirvana production masters with extra songs no one ever heard. There were Chess boxes that just said, ‘Session’. Often there was no other info, no metadata. Who knows what was on those tapes? We’ll never know.”

What a loss. Damn. I didn’t know this story.

This was a tough read simply because it brings back the knowledge of a loss that would have been easily preventable if a little forethought had been applied. That forethought should have started with the fact that the condition of the storage facility in and of itself was lacking even basic protection for what was being stored there. Your writing and research is always impeccable, Mr. Rane.