Dear Gen Xer,

Outside Nyugati Station in Budapest, you’ll find a circus of noise and grime: a slapdash collection of peddlers and addicts, of unsmiling locals and uncertain tourists, an endless array of people on the go.

I used to cut through the station every weekday: once in the morning on my way to work; once on the way back home. I’d decided to leave Prague at the age of 43 and start a new job in a different country. It was a huge mistake.

My manager and I did not get along. My colleagues and I did not get along. If Mr. Rogers had been working there, I doubt I would’ve gotten along with him either. My issues with the company weren’t just cultural or ideological. The revulsion was reptilian.

Nyugati Station was my oasis. A place of escape. Of heavenly repose. I used to dream as I strolled past the tracks that it was me who was traveling to Krakow or Vienna; me who was returning to my beloved Prague, which I should never have left in the first place.

Three weeks into my miserable job, I received an undeserved reprimand from one of the higher-ups. I wanted to tell him to go fuck himself, but bit my tongue and got drunk instead. By the end of the night I couldn’t remember what the higher-up had said. All I knew was that he was a douche; a Silicon Valley sycophant who believed the Salesforce Tower had improved San Francisco’s skyline.

I wobbled home at the end of the night wondering whether I should quit in the morning. But I’d already accepted a relocation bonus to work in the company’s Budapest office. I’d spent most of the bonus securing an apartment and setting myself up for the year ahead. If I reneged on my contract now, I’d have to pay the bonus back. Working for assholes was bad enough. Going into debt to not work for them was even more infuriating.

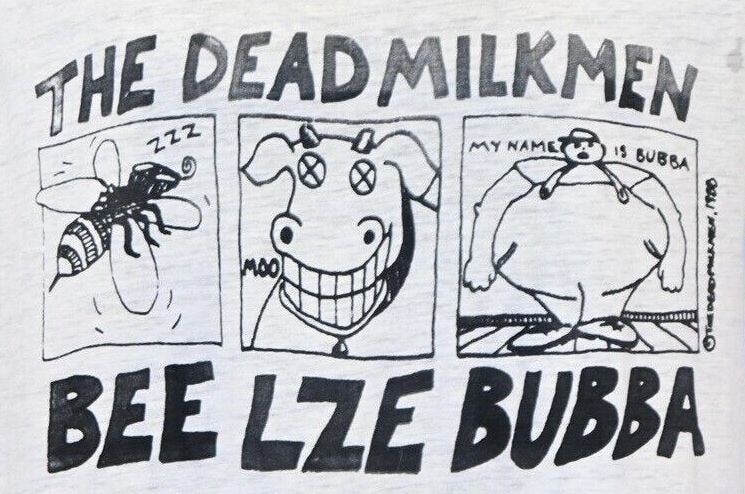

I was approaching Nyugati Station when my thoughts were interrupted by a high-pitched voice. I looked up and saw a middle-aged woman hurrying toward me. She had short spiky hair and eyes as big as saucers. Her jeans were ragged and her boots were scuffed. Covering her wispy frame was an oversized shirt. Printed across the chest was The Dead Milkmen. Under that, a triptych of panels: a bee, a cow, and an overweight dude. Underneath the panels was the word Beelzebubba.

The woman repeated what she’d said. She was close enough now for me to smell her, a scent that was as delightful as a holding cell. Like most of the nighthawks at Nyugati Station, the woman who’d addressed me was homeless.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I don’t speak Hungarian.”

The woman pressed two fingers to her lips, indicating she wanted a smoke. I shrugged my shoulders and shook my head. The woman shrugged back. She was used to disappointment.

“American?” she asked.

“Canadian,” I said.

This was met with more disappointment.

“Change?” she asked.

I dug into my pockets but came up empty. I’d run out of cash while drinking at the bar, and had used my card to settle my tab. As much as I wanted to help the woman, I was fresh out of forints.

I shrugged again and the woman grunted. Clearly, I’d wasted her time. I tried to apologize but she darted off.

I watched her finagle a cigarette from a man who was waiting at a nearby light. Then I cut across Nyugati Station and made my way back home.

Five months passed.

Work still sucked, but I kept on grinding. I’d decided to stick it out because I was saving tons of money. Having no friends or social life helped.

I lived like a monk and fended off my loneliness by going on walks at the end of the day: long, sweaty treks around Margaret Island, up-up-up into the hills of Buda, then rumbling back down and across the Danube, into the bowels of Pest. Finally, I’d arrive at Nyugati Station. I continued to dream as I sauntered past the tracks. And I kept my eyes peeled for Punk Rock Girl.

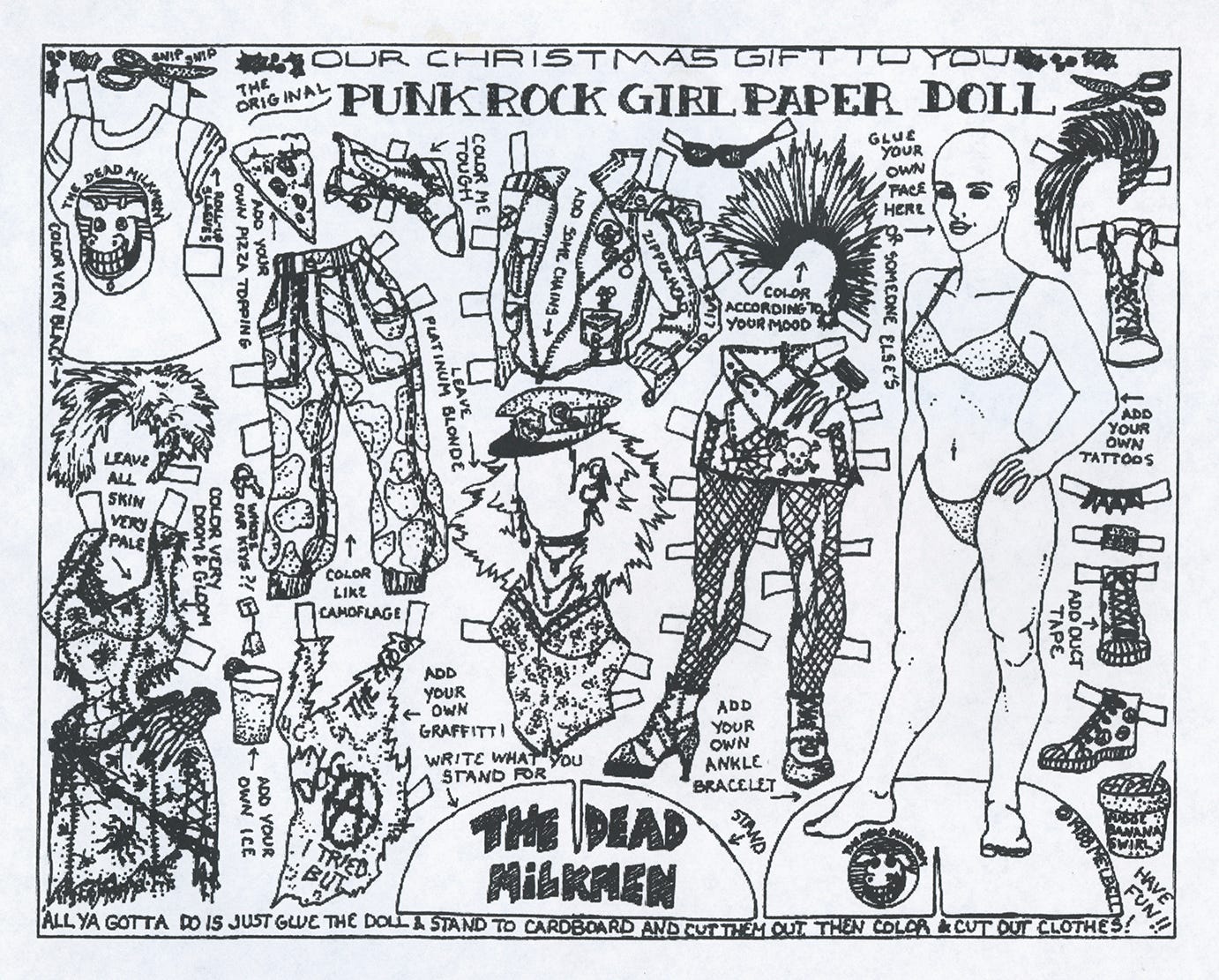

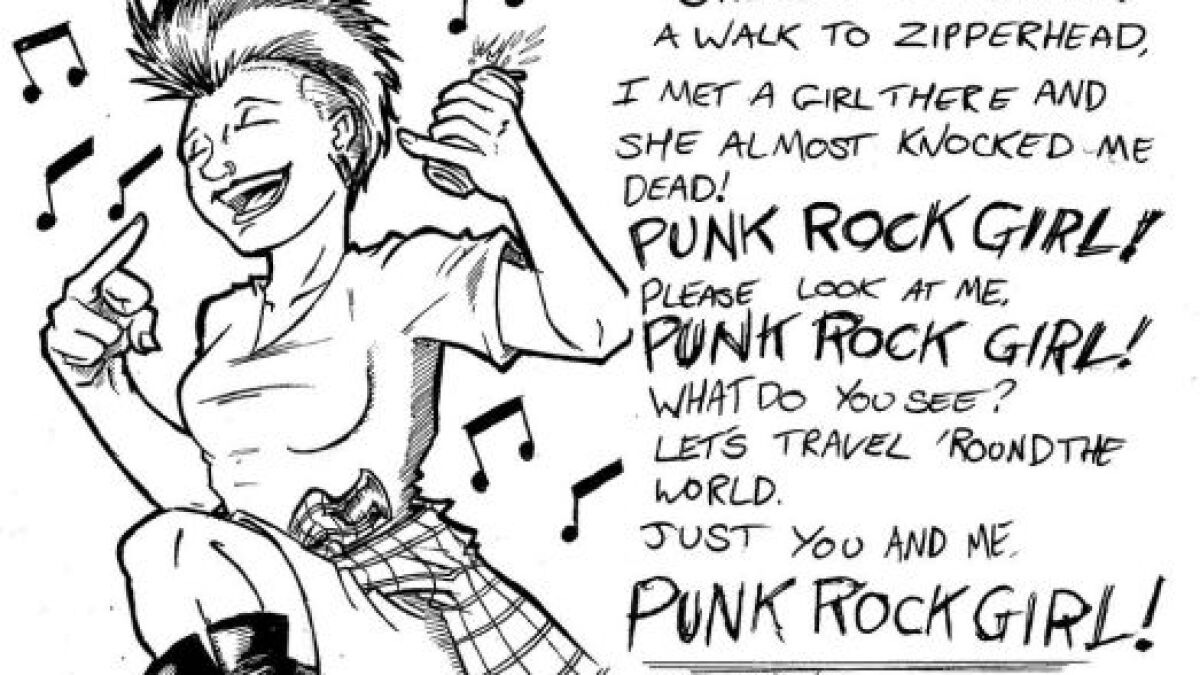

Punk Rock Girl was the name I’d given to the homeless woman in The Dead Milkmen shirt. It was also the title of the only hit song The Dead Milkmen enjoyed.

Punk Rock Girl was the first single off Beelzebubba. It graced the airwaves in 1988 and peaked at #11 the following year on Billboard’s Modern Rock Tracks. It’s a funny, quirky, catchy tune about an average kid in Philadelphia who goes on adventures with a Punk Rock Girl. I used to sing it when I was in university. My friends and I had Beelzebubba on heavy rotation then.

I wondered, at times, while I was on my walks, if Punk Rock Girl ever went to university. What was her story? How did she wind up on the streets?

I don’t know why I kept hoping to see her. Maybe because I’d been unable to help. Maybe because I was intrigued by her shirt. Or maybe because we were about the same age, and I knew deep down that if things hadn’t worked out with my job, I might have wound up on the streets with her, hustling randos for the same hot nickel.

One fall day, I found her.

I was in the mall next to Nyugati Station, shopping for groceries at the supermarket. Punk Rock Girl was hovering around a massive display of cheese. She looked even thinner than I remembered her. Her eyes, which had seemed as big as saucers, now looked like a couple of crop circles, sunk into a face that hadn’t been washed in days.

Punk Rock Girl cast a glance around, then snatched a hunk of cheese from the display and stuffed it into her jacket. She looked around again to see if anyone had caught her. That’s when she locked onto me.

Punk Rock Girl stiffened. She didn’t recognize me, naturally. She was just wondering what I might do.

What I wanted to do was say hello. Fill up a cart with whatever she needed and pay for everything with the money I’d saved. Instead, I looked away and pretended I hadn’t seen her. I acted like she didn’t exist.

A few seconds later, I dared a peek. Punk Rock Girl was gone.

The last time I entered Nyugati Station was the day after my contract at the company was up. I didn’t have to dream about leaving anymore. In my pocket was a ticket back to Prague. I’d started anew at the age of 43, and was doing the same at the age of 44.

I never ran into Punk Rock Girl again. I hoped that meant she’d managed somehow to start a new life as well. Somewhere warm. Somewhere safe. Laughing and loving and singing along to The Dead Milkmen.

Punk’s not dead, I thought, as the train pulled out of Nyugati Station.

Least I hope she ain’t.

That song reminds me of watching Post Modern and 120 Minutes late at night in MTV. Great song that never really made it into the mainstream but anyone who was into alternative then remembers.

I was surprised by how much human crap was in the sidewalks of Budapest. And it was always a bright red, I presume from all that damn paprika they eat.

I started calling it “Poop-rakosh” which I still find hilariously clever, if I do say so myself.