Hardcore: A Primer

Dear Gen Xer,

It was morning in America and the kids were not alright. The boundless suburbs of Southern California seethed with hundreds of weirdos and freaks who loathed the ignorance, greed, and conformism that ruled their stifling environments. Alienated from society, ignored or abused at home, they sought escape from the status quo and wound up creating a culture of their own: one that rejected mainstream life and danced to the sound of their own brutal beat, a music they called “hardcore”.

Hardcore happened between 1980 and 1986.

Essentially, it’s stripped-down punk. It’s fast and angry and in your face: a no-holds-barred, fuck-you attitude that relies more on energy than talent. While many of the bands of the era were terrible, that was hardly the point. New wave music, guitar gods, polished sounds from major labels, all were rejected and unwelcome.

Throughout suburban beach towns and the heart of Orange County, a wave of punks began to swell. The South Bay scene coalesced in a vacant church in Hermosa Beach. That’s where Greg Ginn and his band Black Flag performed, rehearsed, and slept. They’d put on shows in the church’s basement and play for hardcore punks in the know. Meanwhile, kids from Costa Mesa and Huntington Beach were likewise identifying with this angry new music, showing up and throwing down at places like The Cuckoo’s Nest. They loved the music so much, they invented their own dance called the Huntington Beach (or “HB”) Strut. A precursor to slam dancing, participants would strut around in a circle, swinging their arms and smashing the heads of anyone brave or foolish enough to get within their reach.

You could always tell who was hardcore by the way they chose to dress. Many wore ripped up shirts covered with the names of their favorite bands. Blue jeans, leather jackets, and big black boots were also favored. Topping off the look were closely-cropped heads or brightly dyed hair.

It was a look that trumpeted your defiance, your deliberate severance from the goals and mores of the Reagan era. And it brought you heat. This was the time of the long-haired hick, of Lynyrd Skynyrd fanboys cruising in their 4x4’s, hiding out in parking lots, jumping out of shadows with baseball bats and calling you “faggot” while they beat your ass.

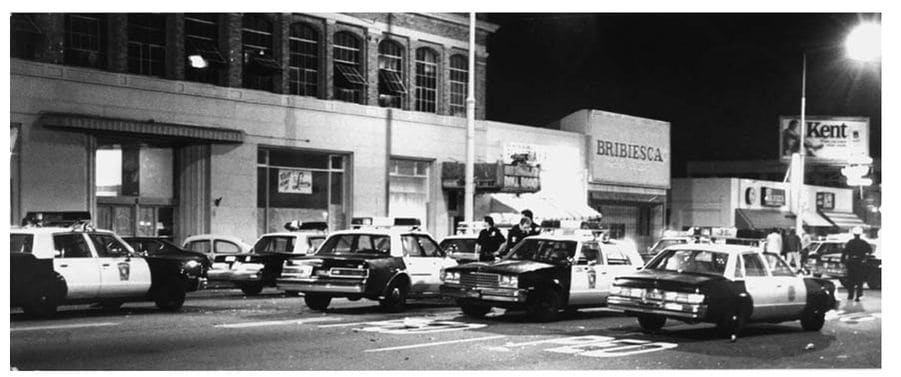

Then there were the cops. They’d crash random shows, break down doors with batons swinging, 30 or 40 at a time, cracking jaws and smashing heads with thin blue line abandon.

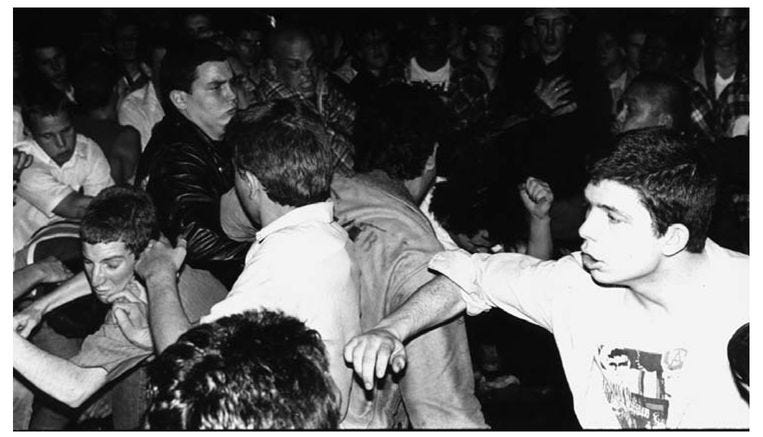

The violence that plagued hardcore kids began to manifest at their shows.

Up until 1981 or so, dancing at punk shows had typically consisted of jumping up and down in one place, otherwise known as “pogoing”. But hardcore punks turned dancing into a sporting event. They formed what came to be known as “The Pit”: a ferocious ring of codified violence, where kids worked up a frenzied sweat, launching themselves into a whirlwind of bodies, risking broken bones and bloody gashes, especially if you didn’t know what you were doing. You could be punished for being in the pit, which made it all the more exciting.

The violence inherent at hardcore shows turned a lot of people away. And yet the scene continued to grow. In cities with a strong artistic presence, in San Francisco and DC, in Boston, Vancouver, and New York, bands like Bad Brains and Dead Kennedys, like Minor Threat and D.O.A., were echoing the roar of radical rebellion.

Meanwhile, Black Flag blazed a trail through Podunk America, playing in any town that would have them, blowing minds at high schools and community centers, derelict clubs nobody had heard of. They’d drive for hours, to Indiana say, play for 50 to 200 people, then stay with the dudes in the opening band or return to the road and head to the next gig. Black Flag carved out territory that had otherwise been uncharted. They formed a tight-knit network of punks who shared information and helped propel a national scene. If a club was bad, if a promoter didn’t pay, if a couch was available in Detroit, word traveled fast.

There were many who saw Black Flag on that tour and went on to form their own hardcore bands. They wrote and learned a handful of songs, played in backyards, basements, and warehouses, in primitive venues in the roughest parts of town, in destitute neighborhoods that opened their eyes to what was really happening. There was no security at these events; no liquor license or insurance. If a kid cracked his head open, too fucking bad. If the cops broke it up or the bathroom got trashed, it was time to find another place. Venues opened and closed all the time. Makeshift was a given.

Punk rock in the 1970’s may have been rebellious, but it still relied on the music industry.

The Clash, The Ramones, The Sex Pistols et al were signed to a variety of major labels. But the labels wanted nothing to do with hardcore. And the feeling was more than mutual.

Hardcore punks rejected society. They wanted something different, something to call their own. So they took command of their circumstances and shaped them to their liking. The hardcore movement marked the first time in contemporary music where shows were put on, networks were forged, songs were written, performed, and sold by kids outside of the music business. This entrepreneurial spirit had a name: D.I.Y.

Alternative Tentacles, SST, Dischord, BYO, and Touch and Go were the first hardcore labels to form during this time. They put out records quickly on microscopic budgets: four-track recordings, eight if you were flush, captured live in one or two takes. They often suffered from subpar recording, though that was hardly a problem. Doing something, doing it, taking control of the world around you was the only thing that mattered.

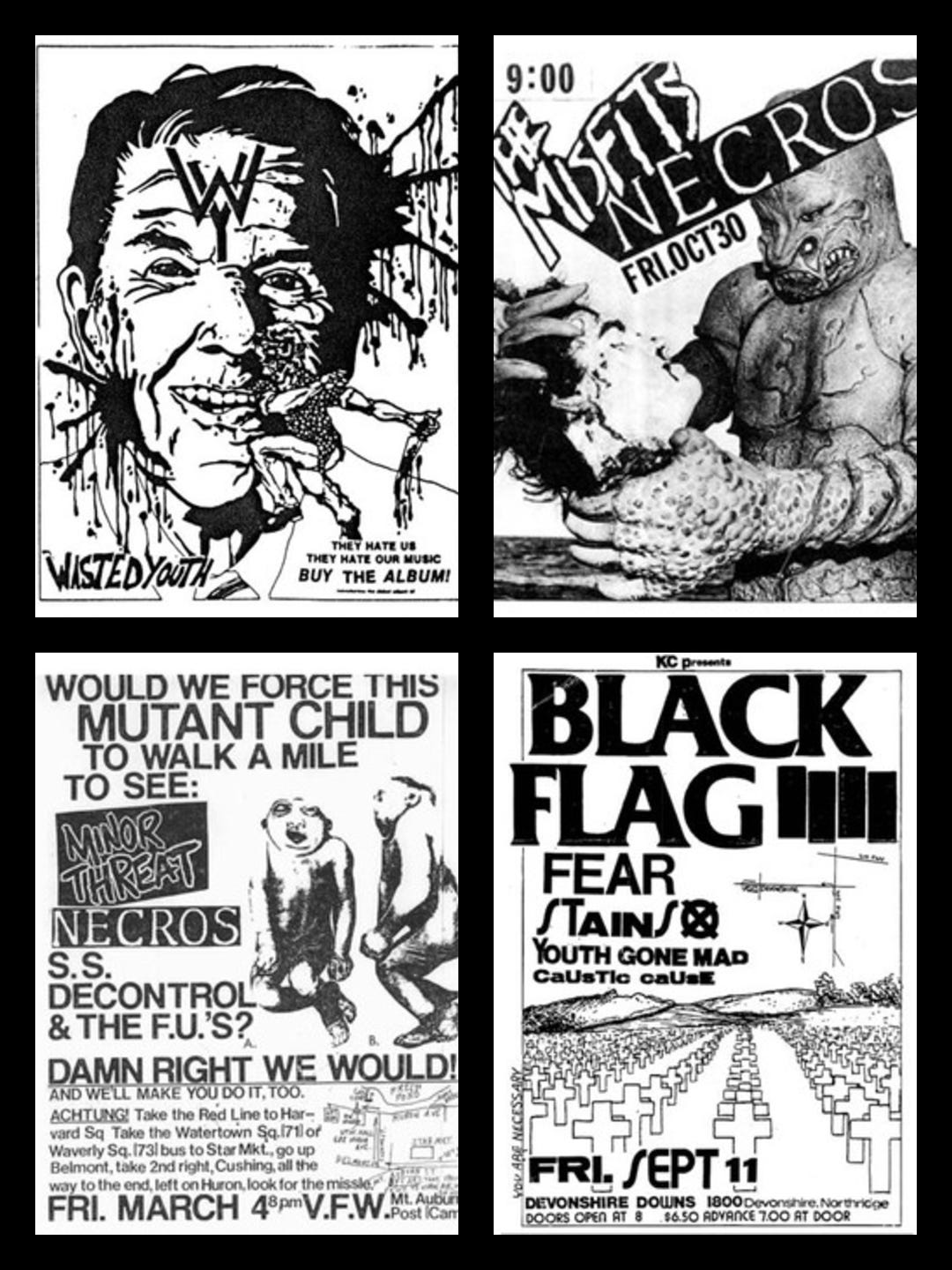

While hardcore inspired a number of musicians, it did the same for anyone else with artistic talent or the desire to develop one. Flyers, fanzines, t-shirts, album covers, all boasted the myriad gifts of burgeoning artists and writers.

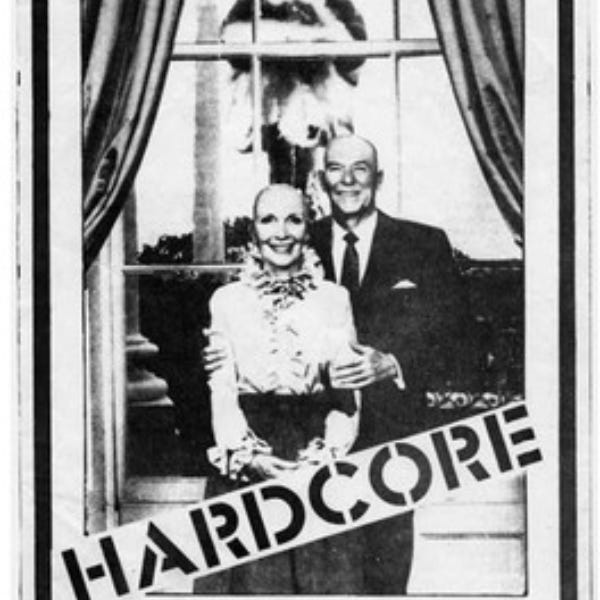

Like the music itself, hardcore art leaned toward the primal. Typically rendered in black and white, the style used illustration, typography, and collage to create striking images that amused punks and challenged the government, the brain-dead consumers, they were railing against.

Collage by its nature is crude and chaotic. It’s an act of vandalism against iconography, the upending of established images. Artists created their own new visions, juxtaposing pornography with mushroom clouds, with Ronald Reagan and the war in Vietnam, powerful statements that captured attention, and you didn’t have to be Michelangelo to do it. You just cut stuff out of magazines and newspapers, did all the lettering by your hand, then mixed it all up and Xeroxed it. The copy machine was a weapon.

Slowly, stubbornly, hardcore was heard.

By the time it reached the mainstream media, the suits at the helm didn’t know what to make of it. So they did what they always do: they demonized the shit out of it. Lurid accounts of violence on the news, laughable dramas with desperate parents and their wayward teens, polluted prime time television. Punk “deprogramming”, championed by ignorant mothers and fathers, by televangelists on the take, was discussed as a legitimate form of “cure”. Parents of punks appeared on shows like Donahue, wringing their hands and wondering how this terrible music and behavior could have possibly happened.

One memorable instance where hardcore met the media occurred when Fear was invited to perform on the 1981 Halloween episode of Saturday Night Live. John Belushi had left the show, but had been invited to do a cameo. Belushi agreed on one condition: Fear would be the musical act. Producer Lorne Michaels got in touch with Penelope Sheeris, who’d recently directed a documentary on the hardcore scene called The Decline of Western Civilization. She, in turn, contacted Ian MacKaye - then the frontman for Minor Threat. She put MacKaye on the phone with Belushi who asked him to come to New York City and show the audience what hardcore was about. MacKaye obliged by arriving with 30 or so punks from DC. Joining them in the audience was a gang of local New York punks.

From the opening note of “Beef Baloney”, all hell broke loose. From stage diving to slam dancing, the punks put on one hell of a show. If you watch Fear’s performance, you can’t help but smile at the exuberance on display. It almost feels surreal that a hardcore band played on SNL. Of course that ended soon after Fear’s second song, when Ian MacKaye grabbed the mic and yelled “New York sucks!”, prompting the show to cut to commercial shortly after. The punks ran out of 30 Rock laughing. Not laughing were the network’s executives. Apparently the hardcore hijinks had caused a lot of damage, $50K - $250K, depending on who you ask.

Whatever the actual total was, Fear’s performance on Saturday Night Live did little to validate the hardcore scene. MTV, who came on air and shot to prominence in 1981, just as hardcore was ramping up, ignored the music completely. They broke down eventually in 1984 with the airing of “Institutionalized” by Suicidal Tendencies. MTV also deigned to play “Alcohol” by Gang Green and “I Against I” by Bad Brains. Those three songs were pretty much it.

Hardcore ended in 1986, with a handful of events spurring its demise.

Pioneer bands Black Flag and Dead Kennedys decided to break up. D-Boon of Minutemen died in a horrific accident. Hüsker Dü signed to Warner Brothers, Minor Threat morphed into Fugazi, and Circle Jerks, TSOL, and a handful of other influential acts began to infuse their music with metal.

Other factors contributed as well. Hardcore’s insistence on a particular sound guaranteed its inability to evolve beyond its strict parameters. As the bands and musicians got older, they craved variety in their artistic expression, an impossible feat if they wanted to remain faithful to hardcore’s tenets.

The music’s lack of commercial viability also proved fatal. Most bands never made any money, while the few who did were hardly rich. Hardcore’s tiny audience, limited demand in a cutthroat market, meant the margin for business error was razor thin at best. And because the bands and labels and distributors were doing everything by themselves, because they were doing it for the very first time, because many of them didn’t know what they were doing, crucial errors were made. In 1984, distributors like Faulty Products in New York, Systematic in San Francisco, and Greenworld in Los Angeles all went belly-up. They owed lots of money to the record labels, money the labels never recouped. Most of those labels didn’t recover. Ditto the musicians they were unable to pay.

There was another reason hardcore died.

Simply put, the times were changing. The kids grew up and went their own ways, some to school, others to jail, a few into the abyss of corporate America.

Meanwhile, harder-edged tastes shifted to metal bands like Slayer and Metallica, who were doing heavy and exciting new things. There were also the rumblings of a new type of music evolving in Seattle, angry sounds that were vaguely familiar.

Hardcore didn’t last very long, and was marginal at best, but its influence is hard to ignore. Mosh pits, stagediving, building your own scene, forming your own network, all of it can be attributed to the alienated and creative misfits who came of age in the early ‘80s.

The kids may not have been alright, but they did what they could to change.

As the title states, this is just an intro to hardcore. For a deeper dive into this fascinating subject, I heartily recommend the following sources:

Books: American Hardcore, Get in the Van, Our Band Could Be Your Life, We Got the Neutron Bomb

Films: American Hardcore, The Decline of Western Civilization

Hardcore was an antidepressant for a lot of us. It helped us cope with some pretty bleak shit.

Today's America could use its own hardcore scene, or something like it, to share anger and fierceness in reaction to the world.

What a great article! It brought back many musical memories. Several of those bands - and their songs - stand the test of time. I still get a thrill listening to the Dead Kennedys, Husker Du, the Minutemen, etc. And, The Decline of Western Civilization is one hell of a film.

Every generation deserves their soundtrack. It’s a shame the soundtrack of today’s youth is so fucking lame. Disco had more fucking muscle.