Dear Gen Xer,

At the hospital, after the shootings, when detectives asked him why they’d done it, James Vance wrote the words LIFE SUCKS.

Life had always sucked for Vance. He’d been forced to repeat the first two grades after he was diagnosed with “extreme hyperactivity”. Vance’s mother, Phyllis, a born-again Christian, claimed later at the trial that she’d ignored recommendations from multiple doctors to treat her son with Ritalin because, “Those kids on Ritalin were zombies.”

One day in second grade, Vance tied a belt around his head and proceeded to yank his hair out. The following year he was expelled for violent behavior and got so enraged when his mother wouldn’t listen to his side of the story that he wrapped his hands around her throat and tried to choke her out. Two years later, he went after her with a hammer.

Vance was placed in Special Ed classes at the age of ten. His classmates were paraplegics and kids with Down’s Syndrome, as well as a boy who’d been unable to speak since swallowing a bottle of bleach when he was three.

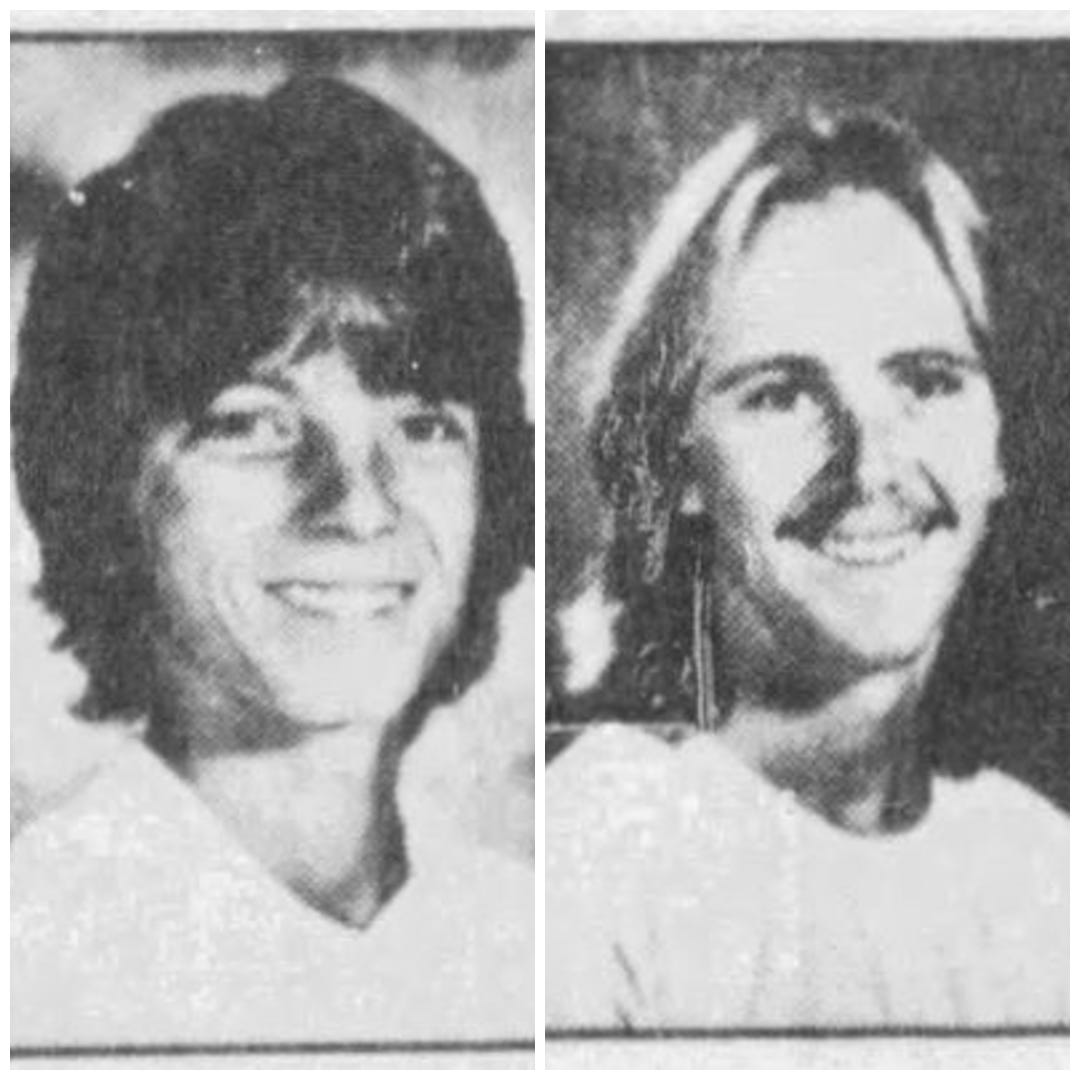

Vance didn’t have any friends to speak of, until he met Raymond Belknap in the sixth grade. Belknap was two years Vance’s junior. He didn’t have any friends either, and seemed to hate everyone, including himself.

The pair of outcasts bonded quickly. They hung out after school, spent their weekends hunting quail, and went to a cave near the edge of town where they would, “nail whole families of bats to the wall with air-rifle shot”.

There wasn’t much else for them to do. Not in boring Sparks, Nevada: a modest city with modest prospects, three miles east of Reno.

Vance and Belknap dropped out of high school in their junior year. Vance bounced around from job to job, washing trucks, cleaning offices, slinging slop at Burger King and Wendy’s. He’d work for a few days, maybe a few weeks, until he lost patience with the gig or the boss and then he’d just say fuck it. Belknap, meanwhile, worked construction. But he kept missing work because mornings were a bitch and eventually they replaced him with someone dependable. Belknap found another job at a used furniture store. Three weeks in, he stole $454 from his boss’s desk, then hopped on a bus to Oklahoma to visit his biological father. One week later, he was back in Sparks, facing trial for his offense.

Belknap received a suspended sentence. He was ordered to go to counselling and was allowed, eventually, to leave the state and live with his father in Oklahoma. It’s unclear what transpired between Belknap and his father, but he was back in Sparks a couple of months later, working at a print shop for ten cents over minimum wage.

Life still sucked. Everything sucked. Except for Judas Priest.

Vance and Belknap loved Judas Priest.

The band’s music amplified the boys’ rebellious spirit. It filled them with power and helped them forget their shitty unfulfilled lives. They’d blast Judas Priest in Belknap’s room and spend the day pounding beer and getting high and dreaming about leaving Sparks and getting jobs as mercenaries. Sometimes, when emotions ran high, when the two best buds were in need of release, they’d play Dreamer Deceiver and allow themselves to cry:

Standing by my window, breathing summer breeze

Saw a figure floating, 'neath the willow trees

Asked us if we were happy, we said we didn't know

Took us by the hands and up we go

There wasn’t any crying, however, on the morning of December 23, 1985. Sure, Belknap had lost his paycheck shooting pool the night before. Yes, he still owed most of the $454 he’d stolen from his former boss. But he had enough money stashed away to procure a present for his buddy Vance: a brand new copy of Stained Class.

Vance started his day a little after noon. By the time he finally got out of the shower, he’d missed his ride to work. A note on the fridge from his mother informed him that she was at her sister’s house. Vance should call if he needed a lift.

Belknap picked him up instead. He drove them back to his house, where he was babysitting his little sister and a few of her annoying friends. The boys retired to Belknap’s room, put on Priest’s Unleashed in the East, then smoked some weed and cracked open a six-pack of Bud.

An hour or so later, Belknap went to warn his sister and her stupid friends to stop running around and slamming doors or he’d bust their fucking heads in. Vance headed for the fridge in the garage to fetch some more beer. He ran into Belknap’s half-sister, Rita, a strong-willed girl who never liked him. Vance didn’t care. He was buzzed and feeling good. Skipping work had been the right call. Next time he went in, he’d quit.

When Vance returned to Belknap’s room, he found his friend with a smile on his face. Belknap reached behind his stereo and pulled out the copy of Stained Class. He placed the record on his turntable and gave the sleeve to Vance. “Merry Christmas, brother,” he said.

The boys hugged and punched each other, then began to dance and bang around the room to the album’s opening song, Exciter.

They listened to the album two or three times before heading to the garage to get more beer. Half an hour later, Vance’s mother arrived with his step-dad. They wanted to drive him to work so he could salvage whatever was left of his shift. How else was he going to pay for his smokes?

But Vance was way too drunk to care about some bullshit job. He chased his mother and step-father out, screaming at them as they scurried away: “Leave me alone!”

The interruption soured the party. All the boys were trying to do was have a good time, which was hard enough in fucking Sparks without their parents, the goddamned world, getting in their way.

Later on, in one of his depositions, Vance would claim that the lyrics to Beyond the Realms of Death - “Keep the world with all its sin / It’s not fit for livin’ in” – clarified in both boys’ minds the struggle they’d dealt with since day one. Life sucked. Vance knew it. Belknap knew it. Even Judas Priest knew it. The answer to life was death.

The boys started trashing Belknap’s room.

They smashed and slashed everything in sight, save for Belknap’s records and bed.

Belknap’s little sister and her friends were crying. They and his half-sister Rita were terrified. Rita called their mother, Aunetta Roberson, who left the casino where she was working and sped straight home.

Vance and Belknap were still going strong when Roberson arrived. She yelled at Belknap and tried to enter his room, but Vance kept her out by wedging a two-by-four into the door jamb. Belknap snagged a couple of shells, along with a sawed-off twelve-gauge he kept, then threw his bedroom window open and crawled outside.

Vance followed him down the alley behind the house, over the six-foot concrete wall bordering the yard of the Community First Church of God. They landed in the churchyard at 5:10 p.m. It was already pitch black out, and well below freezing. The boys had left in such a hurry, all they were wearing were jeans and t-shirts.

Belknap handed Vance a shell. He hopped on the carousel in the corner of the churchyard and loaded up his twelve-gauge. Belknap spun around on the carousel and began to chant, “Do it, do it, do it.”

“Just do it,” Vance said.

Belknap jumped off the carousel. He secured his shotgun on the ground between his feet and stuck the barrel so tight under his chin his words came out clipped. “I sure fucked up my life,” Belknap said, then reached for the trigger and squeezed.

Vance was shaking. He reached for the shotgun that was lying next to his best friend’s body. He placed the shell Belknap had given him slowly into the chamber.

“I didn’t know what to do. I thought somebody was going to stop me.” – James Vance

Vance admitted later that the only reason he’d shot himself was because he was afraid that he’d be blamed for Belknap’s death. He placed the shotgun in his mouth, but it was covered with so much blood it made Vance gag. He secured the gun under his chin instead and stood there thinking for a while about his mother and the people he loved. A few minutes later, Vance heard sirens.

Vance reached down and pulled the trigger. The surface of the gun was so slippery, however, it caused him to miss his eyes and brain. He shot off his chin, his mouth, and nose, before the bullet exited above his cheekbones.

Vance sensed a lightness as he fell to the ground. He remembered feeling numb and then a sting. When the paramedics arrived, they tied Vance to a stretcher and loaded him into the ambulance. He was given an emergency tracheotomy on the way to the hospital to keep him from choking on his own blood and fragments from his face.

Vance had no idea of the damage he’d done. He couldn’t understand why it was so difficult to tell the paramedic he didn’t want to die.

Vance lay in hospital the next three months.

He lived in constant and agonizing pain: before, between, and after over 140 hours of reconstructive surgery. The doctors at Stanford University Hospital began with a flap of Vance’s forehead, the only piece of skin left on his face, which they pulled down gradually with skin extenders. The bulk that formed in the center of his face served as a makeshift nose.

A third of Vance’s tongue remained, though he’d lost his gag reflex after the back of his palette exploded, and he tended to drool or swallow it. One of Vance’s teeth had survived the blast. If he used his thumb as an incisor, he could chew a variety of food.

Two years later, doctors would fashion a pair of lips with skin from the back of Vance’s knee. They also began building his third and final chin, courtesy of bone fragments from Vance’s right shoulder blade.

All the while, the nightmares persisted.

“Jay’d wake up screaming in blind terror in the middle of the night, and I’d be lying right there beside him. It was literally blind terror. His face was so swollen he couldn’t see anything except his dream, the same one, night after night: Ray blowing the back of his head off and the fire coming out.” – Phyllis Vance

Vance was still grieving the death of his friend. He couldn’t believe Belknap was gone. He felt so bad, he wrote his mom a letter.

“I believe that alcohol and Heavy Metal music, such as Judas Priest”, led us or even “mesmerized”, us in to believing the answer to “life was death”.” – James Vance

Belknap’s mother, along with Vance’s, responded by hiring a trio of lawyers. The lawyers filed a product-liability suit against Judas Priest and CBS Records in 1986. The mothers sought $6.2 million in damages ($5 million for Vance, $1.2 for Belknap) to compensate for the wrongful death of Raymond Belknap, and the wrongful injury, plus medical bills, of James Vance.

It took three years for the case to go trial.

That’s because Bill Nickloff, a self-taught audio engineer who’d been hired by the plaintiffs’ lawyers on the strength of his series of subliminal self-help tapes, claimed he’d found the smoking gun on Judas Priest’s Stained Class CD.

Seven smoking guns, actually. Seven subliminal instances when the words “Do it” appeared in the first and second choruses of Better By You, Better Than Me.

Nickloff also concluded that someone other than Rob Halford had uttered the Do its, and that the words had been spread across 11 of the song’s 24 tracks. He was unable to prove this conclusively, however, simply by testing the CD. In order to do so, he’d need to analyze the master tapes.

CBS Records located the master of Better By You, Better Than Me a couple of years later in September 1988. They sent Nickloff a safety copy three months after that. Nickloff alleged that CBS had used that time to hide or remove the embedded Do its.

Nickloff demanded the original master to the song, then refused to examine it when CBS sent it to him. He claimed that the tape’s outer coating of zinc oxide had suspiciously begun to flake, and he didn’t want to be held responsible for any damage that might be caused.

On November 29, 1988, a year and a half before the trial would begin, James Vance died.

He’d been admitted to Washoe Medical Center for treatment of depression on November 15th. Vance lapsed into a coma on Thanksgiving Day. Five days later, he was dead.

Rumors abounded at the time that Vance had deliberately overdosed on methadone. Whether that’s true, or how he could have acquired the lethal dosage, has never been determined.

The trial began on July 16, 1990.

Outside the courthouse, metalheads were banging. They were laughing and smoking and carrying placards, making their presence known. They’d come in full force to support Judas Priest, to show them not everyone in lame-ass Nevada was a victim of Satanic Panic.

Inside the courtroom, Judge Jerry Whitehead presided. A learned and respected man, he alone would deliver a verdict, as both sides had agreed to forego a jury.

Whitehead explained the reason they’d gathered as soon as he sat down:

“Just to make sure that we’re together: there is nothing in the music, in the sound effects, or the lyrics that is actionable because they are constitutionally protected. What is on trial is whether there are subliminal messages present and, if so, if they have an effect upon the listener.” – Judge Whitehead

Attorneys representing the families claimed that the hidden Do its in Judas Priest’s music had invaded the subconscious of Belknap and Vance and compelled them to form a suicide pact. They accused Judas Priest and CBS Records of being masters of deception, of manipulating the minds of fans and listeners, and of enhancing their songs with hidden messages to give them a competitive edge in the marketplace.

Attorneys for Judas Priest and CBS Records argued there were no subliminal messages in any piece of the artist’s music. Nor was there any scientific evidence that proved subliminal messages caused compulsive behavior in people. They also pointed to Belknap and Vance’s rampant drug use, to their inability to hold a job, to the abuse they’d suffered at the hands of their fathers, to Belknap’s obsession with guns, to Vance’s numerous stints in rehab, to the boys’ desire to be mercenaries, to Vance running away 13 times, to Belknap being cited 10 days prior to killing himself for shooting darts at a neighbor’s pet, and to the bleak and desperate future awaiting the two young men.

The first three days of the trial focused on the length of time it took CBS Records to find the master tapes, as well as whether or not subliminal messages could have been added to them. Another two days dealt specifically with the subject of backward lyrics.

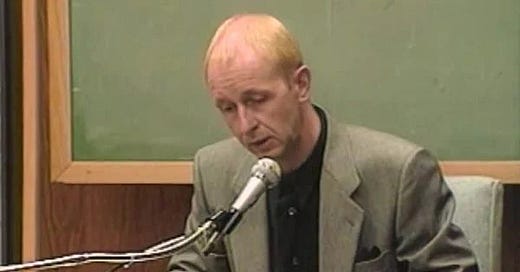

Three-quarters of the testimony came from so-called expert witnesses: audiologists and computer nerds and sketchy psychologists whose performances veered from the eccentric to Oscar worthy. The rest of the testimony came from friends and family of the deceased, as well as from Rob Halford himself, who sang acapella from the stand to demonstrate that the debated Do its were actually inhalations, a benign characteristic of his singing style.

Halford was absent from the courthouse on the morning of the last day of testimony. He arrived later that afternoon with a tape and a double-deck player. Halford claimed that he’d spent the morning in a studio spooling Stained Class backward. He wanted to play what he’d found, if it would please the court.

Lawyers for the plaintiffs objected. Judge Whitehead overruled them. He was curious and wanted to hear the tape.

Halford played a part of the chorus to Exciter, the opening track on Stained Class:

Stand by for Exciter

Salvation is his task

Halford then claimed that if you played the same lyrics backward, you would hear the following:

I asked for a peppermint

I asked for her to get one

Halford hit play.

It wasn’t crystal clear, but it was clear enough to amuse the courtroom. And to make an impression on Judge Whitehead.

“I could literally see his mind clicking and bells and lights going off and thinking: they’re right.” – Rob Halford

Judge Whitehead reached a decision two weeks later.

He criticized CBS Records for their delays during discovery and awarded the plaintiffs’ lawyers $40,000.

Whitehead also determined that the copy of Better By You, Better Than Me that CBS had submitted was authentic and unaltered. He declared that there were several Do its and that they were subliminal, but he believed they’d been placed unintentionally and therefore lacked liability. While Whitehead agreed that the plaintiffs had established sufficient proof of the effectiveness of subliminal stimuli, they’d failed to prove it had been capable of causing the behavior of Belknap and Vance. He dismissed the use of backward lyrics, and while admitting his dislike of heavy metal music, he thanked the members of Judas Priest for their courtesy during the trial.

The case was closed. Judas Priest were free to go.

Whitehead’s verdict was a victory for heavy metal, and for artists everywhere.

“Had the judge found in favor about the so-called subliminal messages having the power to physically manifest themselves and make people to do something, the ramifications of that would’ve been extraordinary. How do you prove to somebody that there are not subliminal messages on your record when you can’t hear them in the first place?” – Rob Halford

35 years after the trial, Judas Priest continues to make music you can hear loud and clear.

They do so minus two of their biggest fans, who had way too much to drink one night and far too little to live for.

Great piece. It reminded me of this hilarious Bill Hicks bit about how nonsensical it is to believe any band wants their audience dead.

"I'm fucking sick of it Nigel. The free money and free drugs, groupies blowing us 24/7, stadiums full of fans. I'm sick of it! There's GOT to be a way out of this. Unless..."

Still there's a lot of overlap between these two guys and the guy who committed the shooting at the Damageplan show. It's unfortunate enough that these guys always seem to find cracks to slip through and even moreso that they find ways to take people with them.

Sparks ain’t so bad. I once won $250 on the nickel slots there passing through to Lake Tahoe. I remember even years prior that there was a bunch of commotion about backwards masking and subliminal messages on analog masters. As we can see now it’s a case of severe mental illness equal to psychotic disorder.